Audio transcription:

I used to live for summer. The other seasons formed one long purgatory to be endured in anticipation of the moment when I could finally flourish under the blazing sun of foreign lands. My self-image depended on cramming as much (mis)adventure as possible into those fleeting months, making sure that when I was forced to return to reality I would at least bring back an impressive tan and some titillating stories. This pressure to stockpile experiences was intensified by the looming prospect of adulthood, which I knew would essentially be defined by saying goodbye to this concept of summer.

Now, an alleged adult, my identity is built around my career, and the energy I once directed towards “living” now goes instead towards “working”. The concept of a holiday has become foreign to me. Travel is still a major part of my life, but only if it’s for an explicit purpose, as if I’m a social vampire who can only enter a country if invited (preferably by an arts institution). The awkward reality is that I don’t actually have much to do in summer, though. My freelance work dries up, it’s too bright to film and it’s too hot to edit. Nevertheless, my workaholic asceticism won’t let me relax. I end up drifting, fidgeting on a continental scale in search of a task that both satisfies my need to accomplish something and lives up to my nostalgic notion of what a summer should be.

2019

Such was the summer of 2019. The documentary that was supposed to keep me busy ended early (filming in August is a terrible idea) and so I dragged myself back to the city, which was muggy, boring, and bereft of anyone I cared about. I spent my days trying to organise a convoluted trip to Finland via Macedonia, while my nights were dedicated to my default activity – watching films.

One fateful evening, I picked out Eric Rohmer’s Green Ray (Le Rayon Vert, 1986), a film I knew nothing about except that it was supposed to be a masterpiece – my preferred level of knowledge/ignorance before a screening. Within minutes, however, I felt the goosebumps that come with entering cinematic nirvana: discovering the perfect film at the perfect moment.

In 1980s Paris, Delphine’s (Marie Rivière) holiday plans are cancelled last minute, leaving her stranded in the stagnant metropolis. Although friends and family offer various solutions, they all require her to mould herself to their plans and adhere to their terms. Desperate, she tries various options only to get frustrated and end up back in the city, trapped in a looping odyssey of malaise. She’s needy, self-absorbed, and whiny, but also totally relatable. As a single woman, she can either be alone or an awkward appendage to a family unit. Nobody understands why, if she isn’t happy in the role of spinster, she doesn’t simply find a boyfriend.

She does eventually meet a man, but in the meantime she becomes obsessed with the titular “green ray” – an elusive, semi-mystical phenomenon whereby a green flash of light appears for a brief moment after sunset, heralding insight and clarity. The film ends with her finally managing to witness the spectacle over the shimmering Mediterranean, without clarifying what resolution it brings for her. Personally, I reject any happy ending predicated on solving narrative conflict by entering into a heteronormative relationship, so I choose to believe that it took the form of coming to terms with being an “outsider” and gaining confidence to be herself.

For me, the great revelation of the film was the solace I found in the rare pleasure of feeling seen on-screen and experiencing a bond of intimacy with Delphine. The film itself was my own green ray – an abstract but beautiful moment of realisation and self-acknowledgement. I was still doomed to drift, but I felt more at peace with it.

2020

These musings felt very distant a year later.

The first stage of lockdown was a process of grieving all the plans I had to cancel. This was followed by relief, concern for loved ones scattered around the globe, and concern for the globe as a whole notwithstanding. Since there was nothing happening to miss out on, I was magically cured of my chronic FOMO. But then of course it all dragged on. I fell back into established habits for dealing with anxiety and took solace in the world of cinema. For some reason, I drifted back to French film, even though I have little relationship to it other than a brief obsession with the Nouvelle Vague as a teenager, an age at which it seemed obligatory, only to move on to the equally predictable step of snubbing it for being too mainstream.

It was late spring and the walls of my one-room apartment began to close in with the promise of impending humidity. On what would have been a Friday night, I tumbled dizzily into the sultry, soporific world of Marguerite Duras’ India Song (1974), a lavish experimental work centred around Anne-Marie Stretter (Delphine Seyrig), the glamourous wife of a French diplomat in 1930s Calcutta. Exhausted by the stifling heat and her own existential ennui, we are first introduced to her as she slumps on the cool floor in the middle of an unbearably hot night, only to be joined by two lovers, who slump down alongside her. Whispering voices off-screen (the only kind we ever hear, as the whole film is constructed with asynchronous sound) offer disjointed snatches of gossip and hearsay, diagnosing her with “leprosy of the heart.”

Almost all the “action” takes place within the confines of the consular mansion. The only glimpse we get of the world outside comes from ominous shots of hauntingly still spaces around the sumptuous estate, as murmurs conjure up unrest, foment, and disease. We never see anything of India itself, emphasising the detachment of the diplomatic bubble from its surroundings and its fundamental disinterest in engaging with the culture it has appointed itself guardian of. In fact, the whole film was shot in a villa in France, which not only demonstrates Duras’ masterful cinematic trickery but also serves as a shrewd commentary on the liminal space inhabited by colonial occupiers. In contrast, the interior world is one of privilege, sensuality and stupor taken to the point of self-destructive excess. Anne-Marie has little agency beyond choosing her lovers, and even that is jeopardised as the narrative unfurls. The core scene of the film is a party in which she dances languorously in and out of the frame, the vivid red of her dress punctuating the lush emerald green of the room. As anonymous as she is, the men orbiting around her are interchangeable and indistinguishable from one another. The construction of the space is abstract and confusing, adding to the disorientation and intoxication. The whole atmosphere is one of empty indulgence for the sake of it, the characters waltzing compulsively but joylessly into oblivion.

At its heart, India Song is a damning dissection of colonial and gender hierarchies, but as a viewing experience it invokes an exquisitely beautiful and painfully tragic world, with its heavy air and palpable fatality, reminding me of the ecstatic potential of film and providing an interlude of catharsis in my own drowsy solitude.

My second and last summer epiphany came courtesy of Frank Beauvais’s experimental documentary Just Don’t Think I’ll Scream (Ne croyez surtout pas que je hurle, 2019). Self-exiled from Paris to the supposed idyll of the French countryside for a failed relationship and with little to distract him from his solitude, Beauvais passes the time watching up to five movies a day. They merge to form a new cinematic universe that is both liberating and oppressive in its limitlessness, as demonstrated by the fact that the entire film consists of one continuous montage of clips.

Over these images, he provides a voiceover in the form of diary entries, meditating on his isolation from the tangible world. He follows the news with horror and helplessness (it is summer 2016, the period of the terrorist attacks in Nice). Eventually, after months of weighing the advantages of country life against the disadvantages of the city – affordability vs. financial struggle, space vs. crowdedness, peace vs. chaos – Beauvais opts for the latter, won over by his need for sociability and to feel included in something again. He packs up his belongings and prepares himself to dismantle his celluloid cocoon.

I would have felt an instant kinship with Beauvais even under normal circumstances, but in the context of lockdown it took on particular poignancy. My descent into cinephilic escapism hadn’t reached the same extent, but I strongly related to the urge to find solace in fictional realms while trying to come to terms with the self-destructive tendency of society. And like Beauvais, I too reached a critical point where I needed to break away from it in favour of human connection.

If my life were a film script, which I often like to imagine that it is, this would have been the perfect ending to my cinematic journey. My meta-itch having been scratched, I would throw open the dusty curtains to bask in the dazzling light of the outside world, but it’s not a happy ending kind of a year and it looks like we’ll be stuck inside for a while yet. Being forced to stay put for so long has me looking back fondly on my summers of shenanigans, reawakening a long-dormant urge to be out in the world for the simple joy of being out in the world. I have a lot of dreams for summer 2021, but if they don’t end up happening at least cinema will be there to give me comfort, like it always has.

Words by Eluned Zoe Aiano

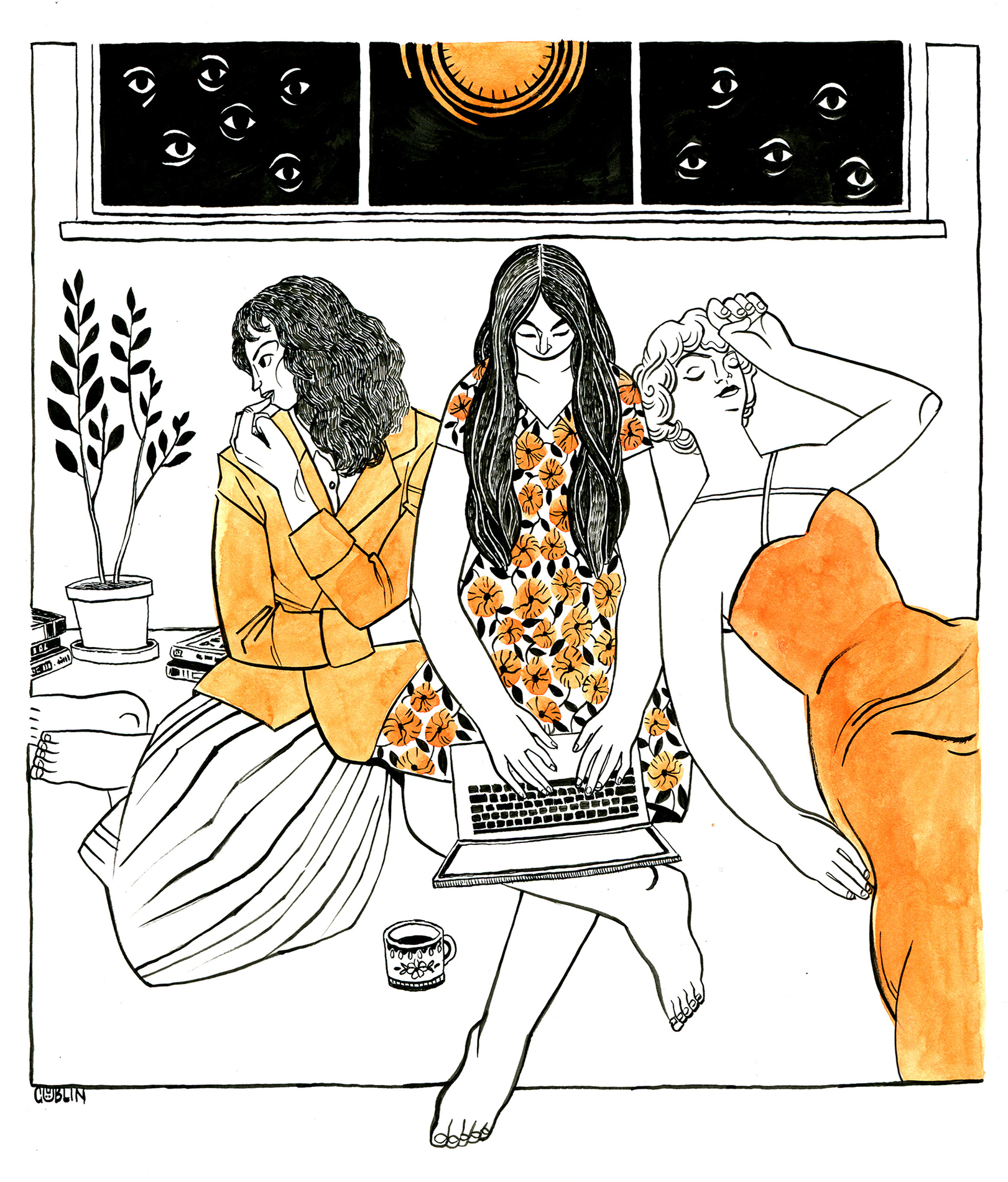

Image by Candice Purwin

Eluned Zoe Aiano is a filmmaker and translator with a background in Visual Anthropology whose work is generally centred on Central/Eastern Europe. She is a founder member of the Wild Pear Arts group in the Balkans, and is currently working on her first feature documentary in Serbia. She also writes about film and is a regular contributor to the East European Film Bulletin.

Candice Purwin is a freelance illustrator and comic book artist based in Edinburgh. Follow her on Instagram at @goblin_purwin.